Data Centres and Energy

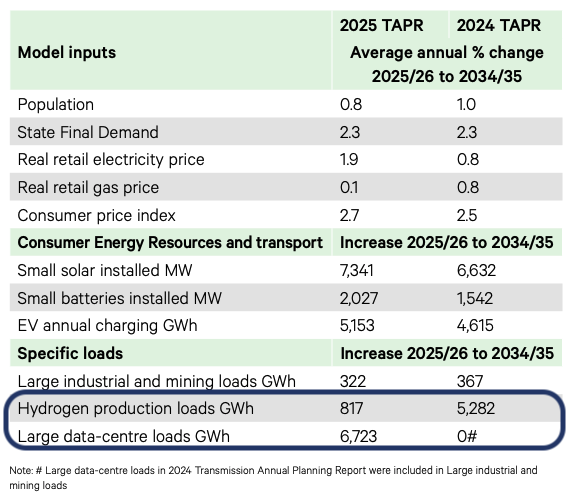

Transgrid’s latest annual planning report had two notable changes in demand in specific load categories. One is hydrogen production with its 2035 forecast falling 85% from 5,282 GWh to 817 GWh. Has the hydrogen bubble burst, or at least rationalised? It seems so. The category to replace it is large data-centre loads, moving from almost 0 in last year’s report to 6,723 GWh forecast in 2035. This is more than expected EV charging demand and around 10% of total NSW demand.

Source: Transgrid 2025 TAPR Medium Scenario

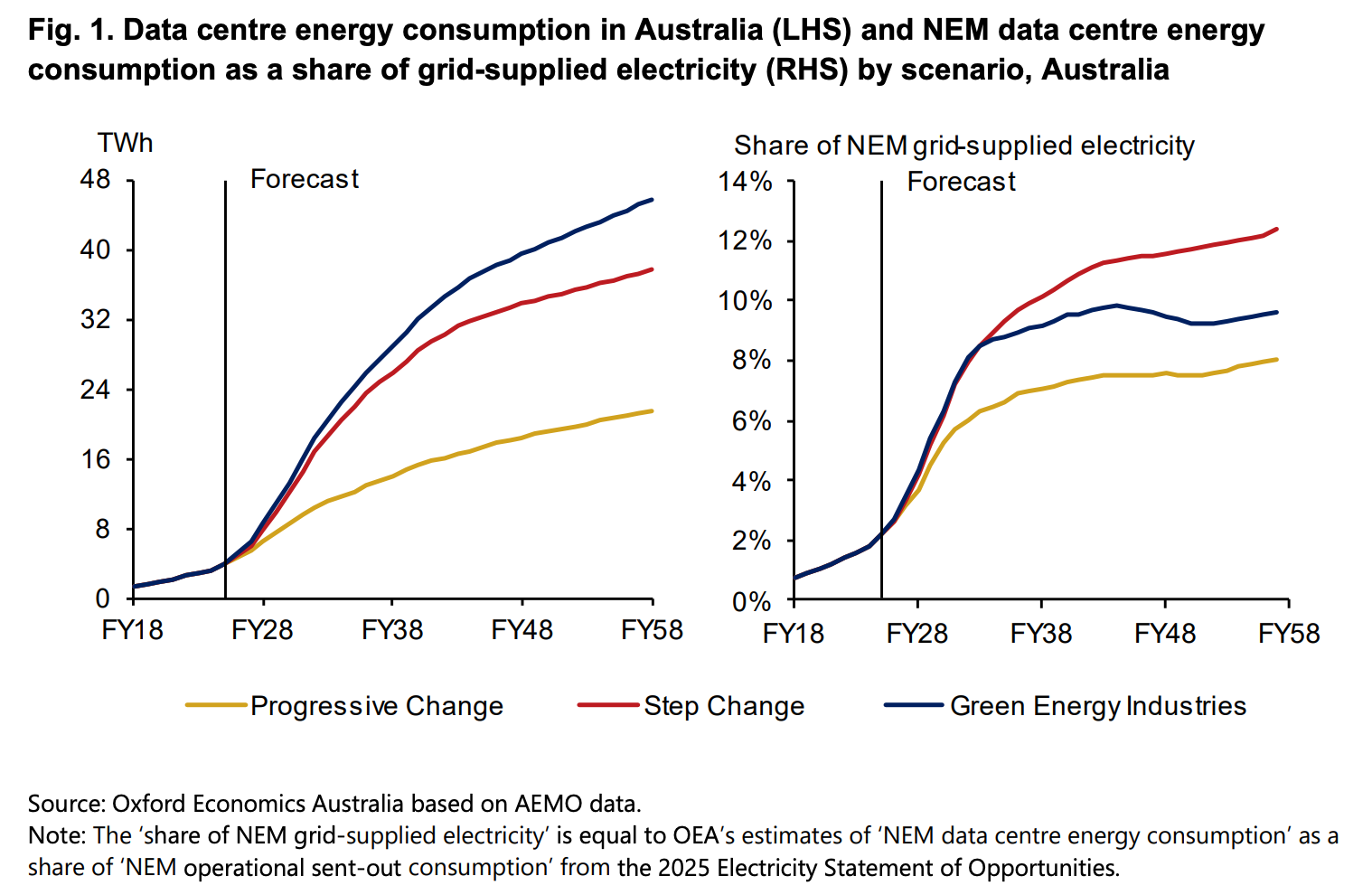

AEMO commissioned Oxford Economics to model data centre uptake and reached similar conclusions, with data centres modelled to take a 6-10% share of electricity in the mid-2030’s and continue to increase from there.

Data centres have been a hot topic in the energy industry, and in Australia planners and the market operator are integrating data centre uptake into their medium-range forecasts. This post covers what’s been driving the increased size of data centres, changes in their design, and barriers they’re encountering.

What’s driving the size of data centres?

Data centre demand is growing and the power density and size of the facilities are increasing. Large data centres are typically in the 50-100MW range, yet we’re now hearing of 400MW facilities or larger being planned.

A driver of this increased data centre power demand is the power density of next-generation graphics processing units (GPUs) used in AI data centres. Data centre GPUs have gone from 10-26kW per rack (a cabinet that houses the chips) in 2020 to 150kW currently and in some cases reaching 600kW by 2027.

GPUs are becoming more energy-efficient, so why are rack power requirements going up? One reason is that there are advantages to networking a large number of chips together. Copper interconnects between GPUs are preferable to fibre optics due to lower costs, power and latency, but copper communications are only effective for a few meters. Therefore, stuffing as much compute as possible within a small space enables higher networking performance.

Below are the power requirements of racks for different generations of enterprise NVIDIA GPUs used in data centres.

| System | GPUs per Rack | Rack Power | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DGX A100 | 32 | 26 kW | 2020 |

| DGX H100 | 32 | 40–50 kW | 2022 |

| DGX H200 | 32 | 40–50 kW | 2024 |

| GB200 NVL72 | 72 | 120 kW | H2 2024 |

| GB300 NVL72 | 72 | 120–150 kW | H2 2025 |

| Vera Rubin NVL144 | 144 | 120–130 kW | H2 2026 |

| Rubin Ultra NVL576 | 576 | 600 kW | H2 2027 |

Of note, demand for Rubin Ultra is much smaller than the base-level Rubin NVL144 and it’s not expected to have large data centres packed with Rubin Ultras. With that said, a row of Rubin Ultra racks would need its own substation.

What's changing in data centre design?

The change in the power density of chips is leading to dramatic changes to the requirements of data centres.

Data centres have to fit an order of magnitude more electrical infrastructure on-site such as switchgear, transformers, backup gensets and uninterruptible power supplies (UPS).

HVAC requirements have changed, with liquid cooling now required for high-end data centre GPUs compared to the air cooling of previous generations.

Customers are seeking new data centres constructed in very short timeframes to house upcoming GPUs which aren’t compatible with existing data centres.

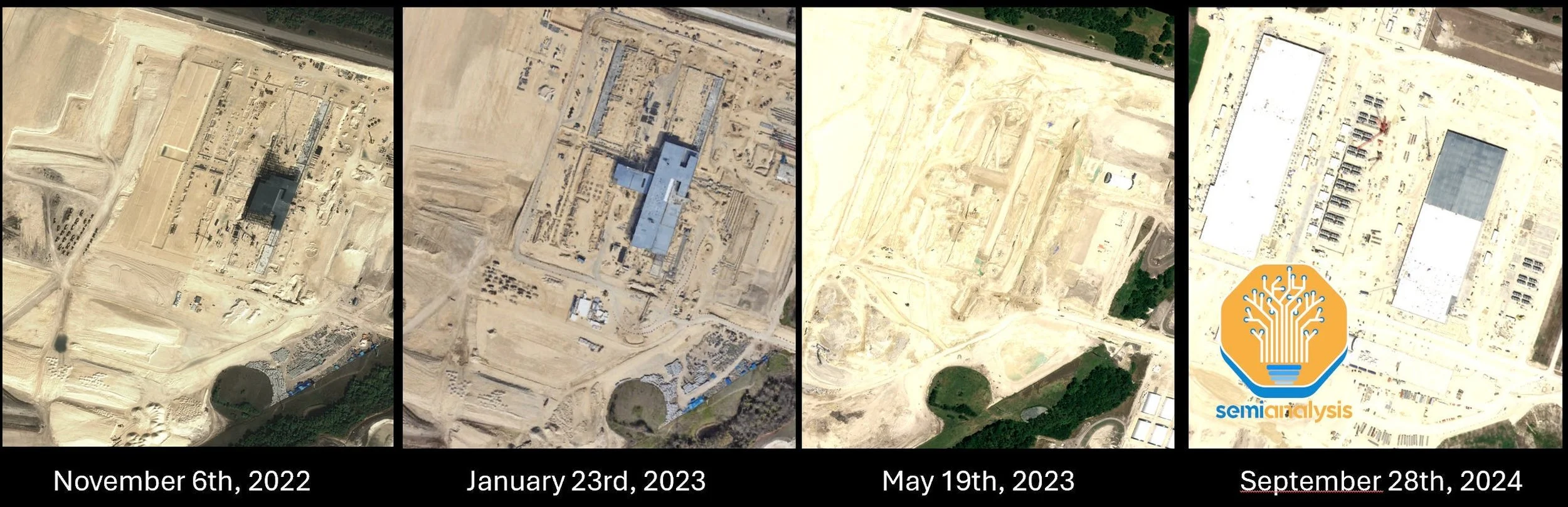

These drivers have led to data centre architecture changes in a short period of time. So short that some data centre projects under construction were demolished to rebuild with a more suitable structure for current generation chips. The images below show a Meta data centre that began with a typical, energy-efficient 'H' design before being demolished and rebuilt with a more modern layout.

Source: SemiAnalysis

These constraints have spurred innovation in data centre designs. Firmus, who for quite a while had been operating a data centre in Tasmania, have commercialised some of their “energy-efficient infrastructure” for AI data centres. This includes water cooling capabilities which are currently particularly valuable. Firmus have recently raised A$330m at an A$1.85 billion valuation.

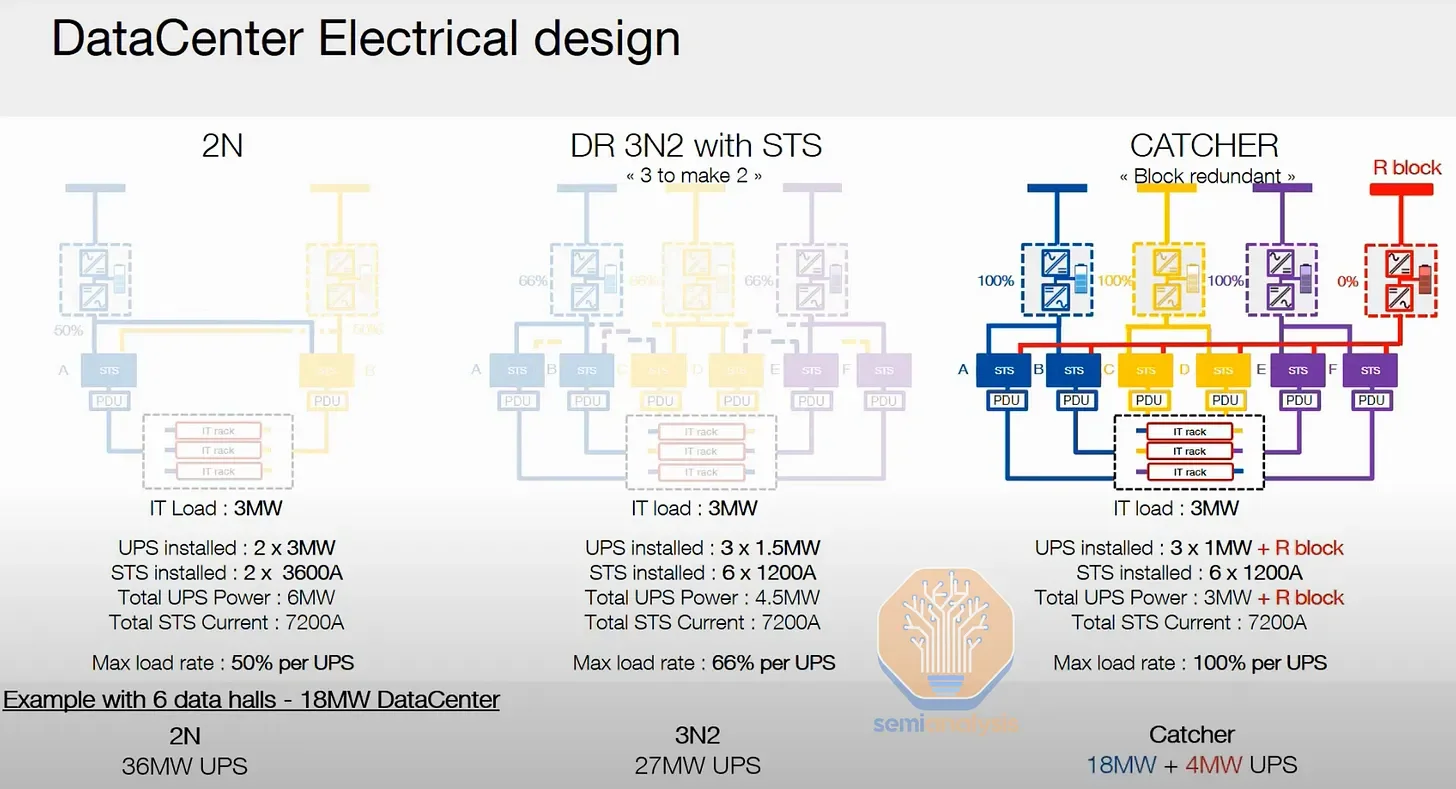

Data centre designers are also experimenting with backup UPS and genset infrastructure, reducing the amount of redundant electrical infrastructure needed to achieve the same level of uptime.

Source: SemiAnalysis/SOCOMEC

Location, location, location

Data centre providers need access to areas with strong connections to electricity, fibre, water, and the workforce. In Australia this means that data centres are currently often being constructted in narrow corridors that fit all these requirements.

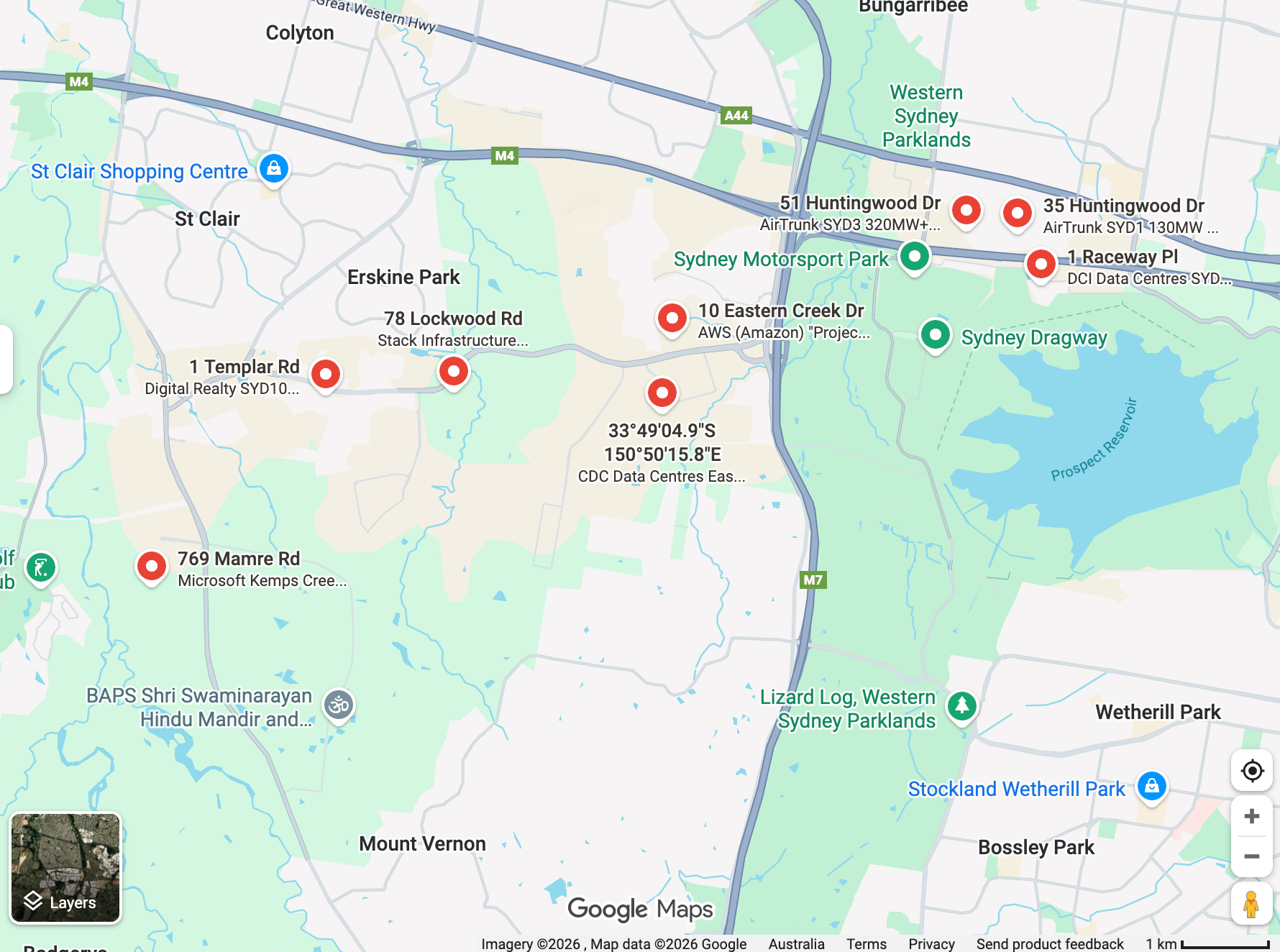

The map below shows the Eastern Creek and surrounding region of Sydney. Each red circle marks a data centre in operation, under construction, or in advanced development. I counted around 4GW of credible projects in development in the Eastern Creek area, with other areas of Sydney such as Macquarie Park receiving a large amount of interest.

Building in such narrow corridors places a significant demand on the existing infrastructure, and limits the ability for on-site renewables to support these facilities and that area of the network. As such, we’ve seen data centre applications be given less network capacity than they had hoped for.

The future

The outlook for AI data centres is uncertain. From an energy requirements perspective in the short term, it seems power density will increase. NVIDIA has showcased an 800V DC architecture to drive greater power density with more energy efficiency and lower copper requirements.

However, technologies like co-packaged optics could enable GPUs to be networked over greater distances, reducing the need to pack compute so tightly. This could mean that currently planned 500MW data centres require less power over time as newer generations become more efficient.

Another question is how many of these facilities will get built. Outside of planning and construction challenges, there’s also a question of when the AI bubble might burst. Data centres, largely financed by debt, are dependent on getting customers into these facilities and payments getting made. Delays to the opening of data centres or some specific customers becoming distressed present risks to most data centre projects.

There are also questions about how much flexibility data centres can provide. This includes whether they can reduce peak demand or run on backup power during grid peaks, or construct on-site renewables and utility-scale BESS. Data centre uptime requirements and locations in Australia may make this harder than it sounds.

The next post explores the opportunity for behind-the-meter energy deployments at AI data centres. Data centres are currently drawing a lot of criticism for their energy and water usage, and their potential to increase emissions or delay the energy transition at a vital time. There are avenues to reduce these negative effects through co-located renewable infrastructure that could potentially outlast and de-risk data centre projects.