May 1, 2023

Mitch O'NeillBootstrapping is a form of starting up. In computer science it’s a small initial program that’s used to load a larger program, in startups it’s trying to build a big company starting with a small amount of resources.

DER aggregators will often naturally fall into this category when building their aggregations. You talk to some customers, get a few of them to sign up their assets in return for value and slowly build your capacity over time. There’s a problem with this idea though. Currently in our markets we have minimum registration sizes. This means that you cannot offer value to those customers until you get a certain number of them.

“Join my aggregator and potentially get $x sometime in the future when enough people join” is not a compelling value proposition, particularly when larger aggregators can offer this value straight away.

It gets worse too when you consider bidding increments, such as bidding in 1MW blocks. This disproportionately impacts smaller participants, holding back a greater proportion of their capacity from the market than bigger players.

“Join my aggregator and potentially get three-quarters of $x sometime in the future when enough people join” is a more accurate representation. $x being the amount that their larger competitor can offer for the equivalent service.

It’s important to note this isn’t an “economies of scales” effect where larger companies can act more efficiently due to size. Those effects are good and we want them in markets. This instead is more like a form of regressive tax imposed on smaller players.

Here are minimum size and increments of two markets DER currently participates in, RERT and FCAS, and the proposed framework for scheduled-lite which is currently pending as rule change:

| Market | Minimum Size | Bid Increment |

|---|---|---|

| RERT | 10MW | 1MW |

| Schedule-lite (proposed) | 5MW | 1MW |

| Contingecy FCAS | 1MW | 1MW |

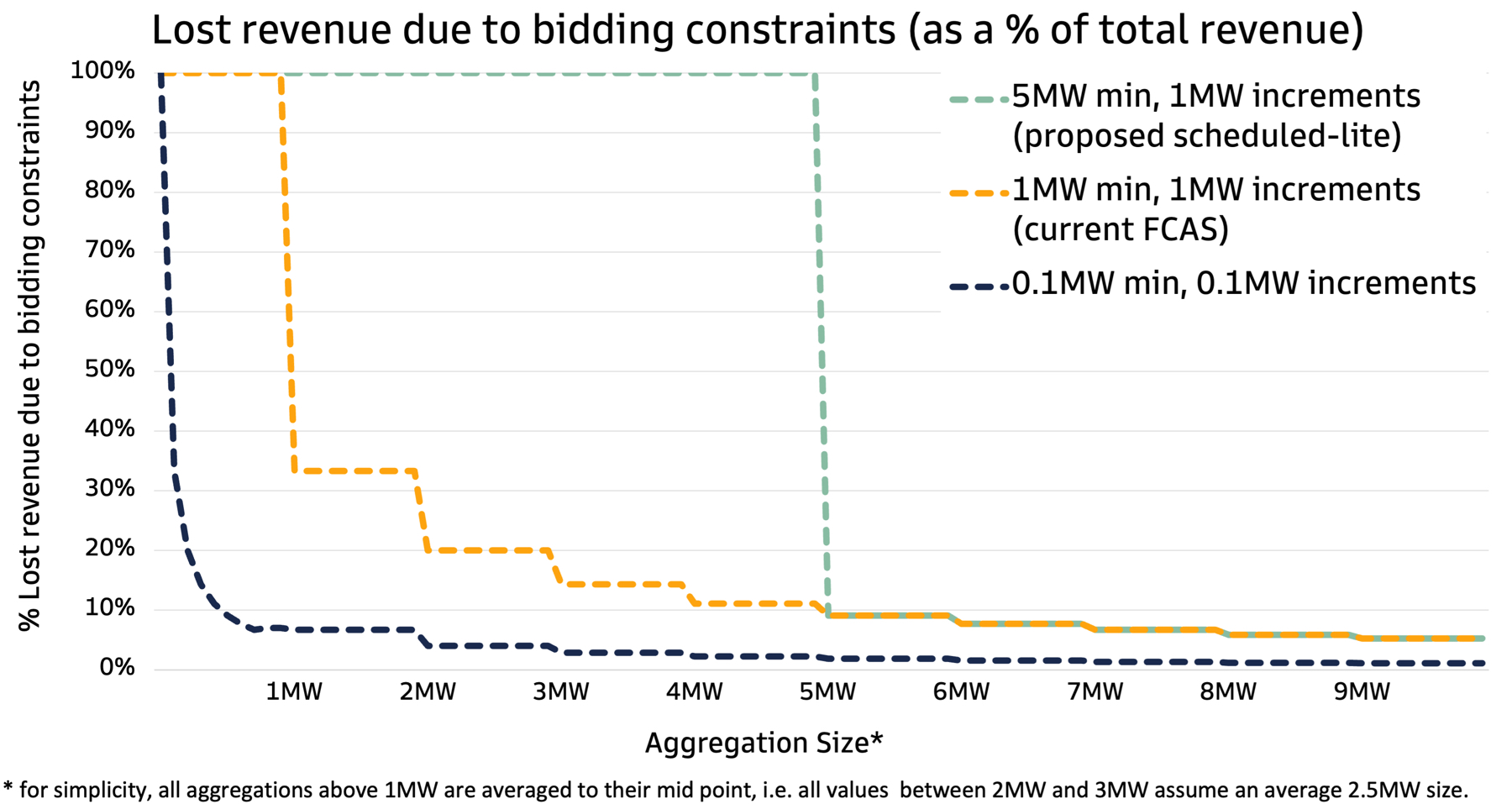

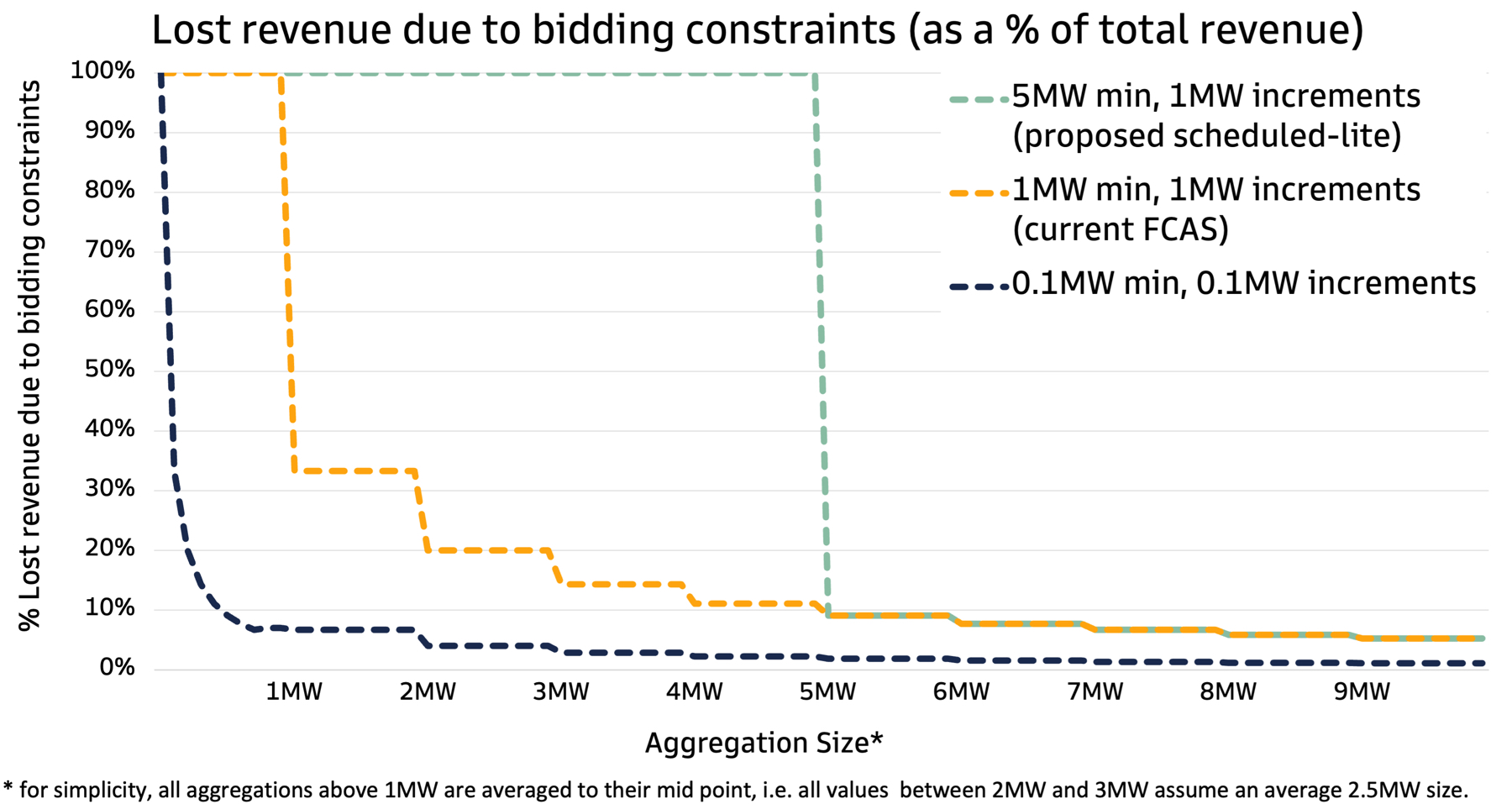

If we map that loss in revenue in scheduled-lite and contingency FCAS against a more ideal framework of 0.1MW minimum registration size and 0.1MW bidding increments, here’s what we get.

An example to understand this: as an aggregator grows between 2 to 3MW it will want to bid 2.5MW on average (assuming linear growth).

RERT wasn’t included as it’s a 100% loss in revenue out to 10MW. Interestingly RERT used to be a 5MW minimum. For completeness, RERT currently has a 5MW minimum in South Australia, but is 10MW for all other mainland states.

These advantages reduce over time but are extremely high in the beginning, creating large barriers for aggregators to enter the market. It’s worthwhile to note that this isn’t applied to the total size of a participant’s aggregation either, it’s applied to the aggregation size per NEM region which makes it much worse.

As loss in revenue stems from the inability to offer capacity in the market, the difference between the lines is therefore a form of “dead weight loss”, an economic term to describe inefficiencies or underutilisation in a market. This deadweight loss doesn’t move to zero after 10MW either, demonstrating that lower bidding increments benefit large aggregations and operators too.

An intuitive argument here may be: why doesn’t this early capacity just aggregate under another, established aggregator? Isn’t that the point of aggregators?

First, this imposes extra cost on the intending market participant. To do this they must integrate their system against the aggregator’s systems, then when they’re large enough integrate directly against AEMO systems. AEMO systems are very old and crusty too so it’s not as simple as just swapping an API over. One interesting tidbit is: AEMO registration fees are cost reflective. This supports the argument that if a participant wants to pay the money to get registered with a small aggregation, then let them.

Second, it can be moderately difficult to impossible to efficiently start your aggregation under another aggregator. “Hey, I’m starting a competing company, according to the Grids blog there’s a large barrier to me entering by myself, can I temporarily join your aggregation to get started?” will probably not be a very successful approach. There are companies that start off as customers of an aggregator, and then go off on their own when bigger. Unfortunately there are things large aggregators can do to make this harder such as installing proprietary hardware on site or through contractual terms (although contracts can only go so far).

It is true that upstart aggregators can offer differentiated value in other ways such as developing projects with customers, creating and implementing bidding strategies or offering a suite of energy services. In spite of this they’ll be competing against the fact that they literally can’t offer as much market revenue as their larger competitors.

The federal government will fund 400 community batteries that they hope will be installed before the next election. Victoria plans to subsidise 100 on top of that. Many of these batteries will be network owned, and leased out to market participants in a competitive tender. Will community groups and upstart aggregators be competitive in these bids? It will be difficult. Even if their costs and capabilities are equivalent to larger players, those larger players can put in better bids due to the higher market revenues and markets they have access to. Having access to scheduled-lite massively benefits the operator of these batteries, primarily due to the energy and FCAS co-optimisation.

Why Does This Matter Now?

Grids blogged about lowering bidding increments a few weeks back thinking it was a largely untested idea. After some research it appears it has been initially tested. AEMO during their scheduled-lite consultation considered 0.1MW bidding increments and small registration sizes. Ultimately though their rule change request proposes 1MW bidding increments and a 5MW minimum size. This is largely due to AEMO costs, particularly changes required to the NEM Dispatch Engine.

In the rule change it states there could be a second stage of work where improvements and extensions can be made. Unfortunately, with a starting date for stage one of 2025, then giving a few years to collect data, a year for the stage two rule change, then two more years to implement it, that puts 2030 as the earliest stage improvements like reduced bidding increments could go live in the market.

Through the schedule-lite consultation process it’s likely there will be further examination of whether the net benefits of implementing lower minimum registration and bidding increments could be improved. Could there be cost efficiencies in updating the bidding increments in other markets (FCAS) or participants (semi-scheduled generators) at the same time? Have the benefits of reduced deadweight loss and improved competition, potentially across multiple markets, been fully considered? Is Grids writing this pretty much ruling itself out from bidding on this CBA due to a perceived or actual conflict of interest?

Imagine if the AER required you to have 5,000 customers signed up before applying to be an energy retailer, or ASIC had a minimum revenue requirement of $500,000/year to register as a company and the ATO rounded up company tax to the nearest $100,000. That’s the kind of world small players exist in right now in the energy market. Hopefully it’ll improve soon.

Thanks for reading.